Carrying Capacity Network

URGENT ACTION ALERT

Negative Impacts of Immigration--Legal and Illegal Amnesty Threat- & Solutions - CCN Alert!

CCN Alert!

carryingcapacity.org

July, 2022

------In 2017 CCN took the lead in calculating the NET (after subtracting taxes immigrants pay) Costs of LEGAL immigration to U.S. taxpayers

and has formulated SOLUTIONS (see below) to the Negative Impacts of both Illegal and Legal

----- And since 2019 Cis,org has published Compendia demonstrating all of these Negative impacts, see below

Net Costs of Legal Immigration to the U.S. Taxpayer

carryingcapacity.org 2017

Unsustainable

1.5 Million Annual Legal-Immigrant Influx

Costs

U.S. Taxpayers $330 Billion NET per Year

Federal

Deficit Faces a $3.3 Trillion Net Hit in Next Decade,

Without

a Reduction in the 1.5 Million Annual Legal-Immigrant Inflow

More

than 5.9 Million Native-Born American Workers Displaced Since 2005

Had

Annual Legal-Immigrant Influx Been Cut to 150,000 per Year Since

2005

Net

Costs to U.S. Taxpayers Would Be $150 Billion per Year at Present

carryingcapacity.org 2017

and from CIS.ORG

A Compendium of Recent Academic Work Showing Negative Impacts of Immigration

By Jason Richwine on June 27, 2022

[Editor's Note: This is the third and most up-to-date edition of the compendium. It was originally published in 2019 and then revised in 2020.]

Introduction

Is there a scholarly consensus that immigration benefits all Americans? Listening to advocates and their allied media, one might assume so. Vox once ran this headline: “There's no evidence that immigrants hurt any American workers.” A writer for Forbes claimed that immigration restrictionists “are on the wrong side of history and the wrong side of social science”. Reason’s Shikha Dalmia has claimed that George Borjas is “literally the only economist of any repute who questions the economic benefits of immigration”.

The purpose of this compendium is to dispel such self-serving myths. The truth is that the costs and benefits of immigration are routinely measured, weighed, and debated in academic journals. No fair reading of the literature could conclude that immigration has only benefits — or only costs, for that matter. A 2016 review by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine demonstrated the mixed effects of immigration, as have dozens of studies appearing since that time. This compendium uses the National Academies as a starting point, then summarizes a sample of subsequently published papers that find costs associated with immigration. These papers address the labor market impact of immigration as well as broader effects.

The National Academies’ 2016 Review

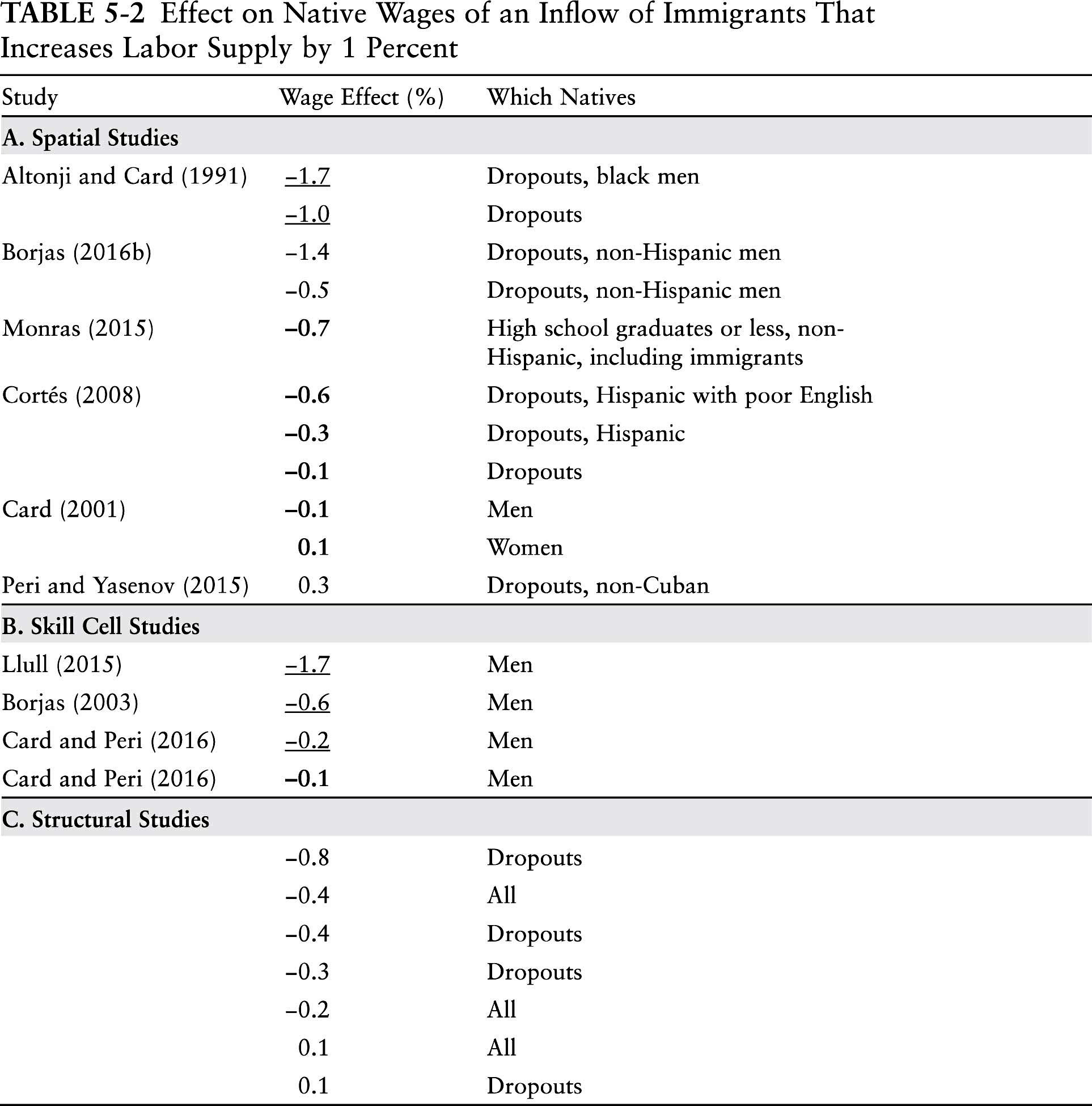

Chapters 4 and 5 of the National Academies’ book-length report review the theoretical and empirical research on how immigration affects wages and employment. Anyone who takes the time to read this material will understand that immigration is costly to certain groups of Americans. For example, Table 5-2 from the report lists several major studies measuring immigration’s impact on wages. Notice the negative values in the “Wage Effect” column:

Unfortunately, not everyone has done the reading. The economist-activist Esther Duflo once told a whopper about the National Academies’ report. According to her, the report “summarized maybe hundreds of studies, and they all come to the conclusion that the effect of low-skilled migration on low-skilled wages is zero.” It is these types of assertions, thoroughly unmoored from reality, that fuel the impression of consensus about immigration’s benefits.

Recent Studies

Since the National Academies’ report was published in 2016, academics have continued to produce papers finding costs associated with immigration. A curated list of these recent papers is provided below. Please note that the authors are mainstream academics writing for mainstream outlets. Harvard’s George Borjas, who was alleged to be “the only economist” to publish these types of studies, clearly has a lot of company. Like Borjas, these authors usually stress that they have found both costs and benefits. One-sided claims about immigration are rarely true.

In each of the following paper summaries, I focus on the immigration aspects of the paper, draw out policy implications, and link to related CIS research whenever helpful.

Wage and Employment Effects

Anthony

Edo, “The

Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market”, Journal of

Economic Surveys, Vol. 33, No. 3, July 2019.

This

review paper is similar in content to the National Academies’

chapters, but it takes a more international perspective. After

considering over 50 studies of immigration in developed countries,

the author concludes that “immigration can create winners and

losers among the native-born workers.” Because low-skill

immigration tends to make low-skill natives the “losers”

and high-skill natives the “winners”, rising inequality

is a natural consequence. This conclusion stands in stark contrast

to the advocates’ position that “there is no evidence

that immigrants hurt any American workers.” While some

Americans gain from immigration, others certainly do lose.

Joseph

Price, Christian vom Lehn, and Riley Wilson, “The

Winners and Losers of Immigration: Evidence from Linked Historical

Data”, NBER Working Paper No. 27156, May 2020.

This

paper acknowledges the winner-loser framework right in its title.

The authors use genealogical data to track millions of men between

decennial censuses in the early 20th century. Following these

individuals allows the authors to improve upon past research that

focused only on community-level impacts of immigration. They find

that older and higher-skilled workers were the “winners”

— their incomes tended to go up when immigrants entered their

local labor market. By contrast, younger and less-skilled workers

were the “losers” — they were more likely to move

away and suffer income losses as a result of immigration.

In

the modern-day context, CIS has emphasized that immigration tends to

have strong disemployment effects on the youngest and least-skilled

Americans of all: teenagers.

David

A. Jaeger, Joakim Ruist, and Jan Stuhler, “Shift-Share

Instruments and the Impact of Immigration”, NBER Working

Paper No. 24285, February 2018.

Several

studies try to isolate the impact of immigration on wages by

comparing cities with different levels of immigration. The problem

is that immigrants do not choose destination cities randomly. If

they choose cities that have rising wages, the negative impact of

immigration may be obscured.

This paper shows that

a common “instrumental variables” technique to deal with

that problem still unintentionally captures more than just the

initial impact of immigration. When a local area experiences an

influx of immigrants, the wage goes down for a time, but then it

rises back toward equilibrium as more businesses come in or other

workers leave. Since immigrants tend to go to the same places year

after year, the instrumental-variables technique captures both the

negative short-term wage effect and

the positive "catch-up" wage effect from earlier waves of

immigrants. As a result, all of the short-term wage effects

estimated using this method appear less negative than they really

are.

The authors of this paper provide a long list

of prior studies that underestimate negative wage effects because of

this faulty method. Giovanni Peri, an economist famous for

downplaying the negative impact of immigration, has 12 different

papers on the list.

Michael

Amior and Alan Manning, “Monopsony

and the Wage Effects of Migration”, CEP Discussion Paper

No. 1690, May 2021.

In

the standard model first developed by George Borjas, immigrants

produce small economic gains for natives (an “immigration

surplus”) but do so by lowering the wages of competing

workers. The model is built on the assumption of “perfect

competition” in the labor market, meaning that employers

compete for labor until the wage is bid up to equal the workers’

value added. But what happens if the assumption of perfect

competition is relaxed?

The authors of this paper

argue that various legal and cultural barriers prevent immigrants

from moving between jobs as easily as natives do. With less

competition among employers to hire workers, immigration could

reduce the ability of workers to demand a wage that reflects the

full value of their labor. If so, both the surplus and the

corresponding wage reductions would increase in magnitude.

L.

Jason Anastasopoulos, George J. Borjas, Gavin G. Cook, and Michael

Lachanski, “Job

Vacancies and Immigration: Evidence from the Mariel Supply Shock”,

Journal of Human Capital, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2021.

It

may seem that the Mariel Boatlift (summarized here

by CIS) has been studied to death, but this is an innovative paper.

It uses a database of historical job listings to establish that job

vacancies for low-skill workers in Miami declined after a sudden

wave of Cuban refugees arrived in the city in 1980. The implication

is that the labor market was not able to immediately adjust to the

influx of new workers.

Christian

Dustmann, Uta Schönberg, and Jan Stuhler, “Labor

Supply Shocks, Native Wages, and the Adjustment of Local

Employment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 132, No.

1., 2017.

Maria

Forthun Hoen, “Immigration

and the Tower of Babel: Using Language Barriers to Identify

Individual Labor Market Effects of Immigration”, Labour

Economics, Vol. 65, 2020.

These

two papers analyze immigration surges in different countries but

come to similar conclusions. In the first paper, a change in

commuting policy led to a sudden increase in Czech workers in a

border area of Germany. The result was lower wages and employment

levels for natives, particularly for those who were older and had

less attachment to the labor force. In the second paper, an

expansion of the EU labor market caused a surge of immigration to

Norway. Wages for young workers fell in the most affected

industries, and workers of all ages — especially older ones —

experienced declines in employment and increases in disability

enrollment.

Although these two papers focus on

Europe, they have important implications for U.S. policy. As CIS has

argued,

the tight labor market in the U.S. in 2019 led employers to recruit

from marginalized groups such as high school dropouts and the

disabled. Expanding immigration in a tight labor market could

short-circuit that employer outreach.

Michael

Amior, “The

Contribution of Immigration to Local Labor Market Adjustment”,

CEP Discussion Paper No. 1678, September 2021.

Why

don’t more Americans leave economically depressed places and

move to the parts of the U.S. where more jobs are available? One

answer, according to this paper, is that foreign immigration crowds

them out. New immigrants tend to settle in high-employment areas,

reducing the potential rewards for natives who move there. This

phenomenon again illustrates how immigration can limit the

opportunities for down-and-out natives to benefit from economic

growth.

Javier

Ortega and Gregory Verdugo, “Who

Stays and Who Leaves? Immigration and the Selection of Natives

Across Locations”, Journal of Economic Geography, Vol. 22,

No. 2, March 2022.

George

J. Borjas and Anthony Edo, “Gender,

Selection into Employment, and the Wage Impact of Immigration”,

NBER Working Paper No. 28682, February 2022. Both

of these papers show that immigration in France has imposed downward

pressure on wages and encouraged natives to move away from

high-immigration areas or leave the labor force entirely. Because

the natives who exit tend to be less-skilled, the wage impact of

immigration on a particular area may be understated if researchers

do not take into account the new workforce composition.

Joan

Monras, “Local

Adjustment to Immigrant-Driven Labor Supply Shocks”,

Journal of Human Capital, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2021.

This

is another paper that demonstrates how internal migration can

partially disguise longer-term labor market effects of immigration.

After the Mariel boatlift initially caused wages to decline in

Miami, the labor market returned to equilibrium. However, about half

of the adaptation can be ascribed to low-skill workers moving away

from (or declining to move to) Miami.

Bin

Xie, “The

Effects of Immigration Quotas on Wages, the Great Black Migration,

and Industrial Development”, IZA Discussion Paper No.

11214, December 2017.

Just

as economists have studied sudden surges in immigration to assess

the labor market effects, the results of sudden restrictions on

immigration are also instructive. According to this analysis,

restrictive immigration laws in the 1920s raised manufacturing wages

and drew black migrants from the South into northern factories. This

result provides further support for the theory that immigration

deters natives from moving into emerging labor

markets.

Interestingly, immigration restriction

also appears to have slowed the growth of electric-powered assembly

lines, which illustrates how the relationship between skills and

technology has changed over time. Low-skill workers were once needed

to man the assembly lines that displaced skilled artisans. Today,

technology generally advances with skilled workers — e.g.,

computer programmers in Silicon Valley. (See the Brunello et

al.

paper listed below for more on this point.)

Ran

Abramitzky, Philipp Ager, Leah Boustan, Elior Cohen, and Casper W.

Hansen, “The

Effect of Immigration Restrictions on Local Labor Markets: Lessons

from the 1920s Border Closure”, American Economic Journal:

Applied Economics, forthcoming.

This

paper also finds that 1920s immigration restrictions benefited rural

Americans who migrated into cities to replace lost labor. In

contrast, farmers mechanized rather than attempting to recruit new

workers.

Amy

Wax and Jason Richwine, “Low-Skill

Immigration: A Case for Restriction”, American Affairs,

Winter 2017.

The

authors combine the “top-down” Census Bureau data on

native job losses with “bottom-up” ethnographic research

on employer preferences for immigrant labor. They make a strong

qualitative case that businesses use immigrants to replace natives

in their low-skill workforces.

In 2019, CIS

published a follow-up

report that focused on Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

cases in which employers are accused of favoring immigrant workers

over native workers. The details of these cases are consistent with

the claim that employers use immigration to depress wages and

working conditions.

Maria

Hoen, Simen Markussen, and Knut Roed, “Immigration

and Economic Mobility”, Journal of Population Economics,

2021.

Using

administrative data from Norway, the authors find that low-skill

immigration has reduced social mobility, causing inequality to

increase. Interestingly, they connect their findings to the politics

of immigration. Opposition to immigration from lower classes in

Norway arises not necessarily from “bigotry”, but as a

rational response to their weakened economic position.

David

Neumark and Cortnie Shupe, “Declining

Teen Employment: Minimum Wages, Other Explanations, and Implications

for Human Capital Investment”, Labour Economics, Vol. 59,

2019.

The

primary focus of this paper is the minimum wage, but it finds some

role for immigration in reducing teen employment. In contrast, the

authors find only minimal evidence that teens voluntarily left the

labor market because the economic returns to a high school diploma

had increased.

Anthony

Edo and Hillel Rapoport, “Minimum

Wages and the Labor Market Effects of Immigration”, Labour

Economics, Vol. 61, December 2019.

This

paper uses state variation in minimum wage laws to show that

immigrants tend to lower the wages and employment levels of the

natives with whom they compete most directly. Specifically, natives

suffer greater wage and employment losses due to low-skill

immigration in states with lower minimum wages. Whether increasing

the minimum wage would be wise policy is beyond the scope of the

paper, but it does show once again that immigrants and natives are —

at least to a large extent — substitutes

in the labor market.

John

Bound, Guarav Khanna, and Nicolas Morales, “Understanding

the Economic Impact of the H-1B Program on the U.S”, in

High-Skilled

Migration to the United States and Its Economic Consequences,

Eds. Gordon H. Hanson, William R. Kerr, and Sarah Turner, University

of Chicago Press, 2018.

General

equilibrium models can be highly sensitive to assumptions. It

sometimes seems that one can build a model to prove virtually any

proposition. In this case, however, the model confirms basic

economic theory: High-skill immigration in the 1990s lowered the

wage for competing native workers but reduced consumer prices and

increased corporate profits, again illustrating the trade-offs

inherent to immigration policy. Consumers and corporations win,

while some workers lose.

Giorgio

Brunello, Elisabetta Lodigiani, and Lorenzo Rocco, “Does

Low-skilled Immigration Increase Profits? Evidence from Italian

Local Labour Markets”, Regional Science and Urban

Economics, Vol. 85, November 2020.

Though

its results are likely underestimated due to use of the

instrumental-variables technique discussed in the Jaeger et

al.

paper listed above, this paper finds the usual result that low-skill

immigration reduces wages and increases profits in affected

industries. The authors speculate that low-skill immigration has

retarded Italy’s transition to a more high-tech

economy.

There is an interesting parallel here to

U.S. agriculture, where CIS research has found that immigration

delays

mechanization of the harvest. (Also see the Abramitzky et

al.

paper above.)

Simone

Bertoli and Steven Stillman, “All

That Glitters Is Not Gold: Wages and Education for U.S. Immigrants”,

Labour Economics, Vol. 61, December 2019.

Education

generally correlates with earnings, but the relationship is weaker

among immigrants. This paper finds that when a highly-educated

immigrant is selected at random, 25 percent of the time he or she

will have lower

earnings than a less-educated immigrant who is also selected at

random. The corresponding figure for high- versus less-educated

natives is about 14 percent. “Conferring a pivotal role to

education in the selection of migrants might fail to induce a

substantial increase in their average quality, and it might even

potentially backfire,” the authors warn. For one thing, these

allegedly “skilled” workers could end up competing with

less-educated natives.

The findings are consistent

with several reports published by CIS. First, despite their faster

educational gains, recent immigrants have not

improved relative to natives on measures of income, poverty, and

welfare consumption. Second, college-educated immigrants are more

likely than college-educated natives to hold low-skill jobs,

especially when the immigrants are from Latin America. Third,

immigrants with foreign

college or advanced degrees score lower on tests of English

literacy, numeracy, and computer operations compared to natives with

the same level of education. Finally, the value

of foreign degrees varies substantially by source country.

Cultural and Political Effects

Kathleen

Kürschner Rauck and Michael Kvasnicka, “The

2015 European Refugee Crisis and Residential Housing Rents in

Germany”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 12047, December

2018.

Kathleen

Kürschner Rauck, “Not

in My Backyard! The 2015 Refugee Crisis in Germany”,

Working Paper on Finance 2020/04, September 2020.

These

companion papers fall at the intersection of economics and culture.

They find that the influx of Syrian refugees to Germany lowered

apartment rents and the prices of single-family homes in areas where

the refugees were most concentrated, despite the sheer increase in

people needing housing. The reason is that native Germans did not

wish to live near large numbers of refugees. Immigration changes

host countries in a variety of ways, and these papers offer a rare

quantitative look at how natives sometimes avoid the areas most

affected.

Umair

Ali, “Native

Flight Responses to Immigration: Evidence from K-12 School

Enrollments”, EdWorkingPaper No. 22-579, May 2022.

In

the U.S., a growing immigrant population in a metropolitan area

increases the likelihood that white and black natives will exit the

public schools. The effect is especially strong among white

students, who tend to move over to private schools. By contrast,

Hispanic and Asian students do not leave the public schools. The

author of this paper suggests that “homophily” —

the desire for cultural familiarity — can explain why

immigration appears to be so disruptive to the student body. Lower

levels of immigration would of course mitigate these cultural

disruptions, as CIS has emphasized.

Courtney

Brell, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston, “The

Labor Market Integration of Refugee Migrants in High-Income

Countries”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No.

1, Winter 2020.

Resettling

refugees may be a humanitarian good, but the argument that refugees

are somehow an economic boon to their host nations is dubious. This

paper reviews the evidence that refugees struggle to integrate into

the economies of high-income host nations. In the U.S. specifically,

refugees perform unusually well in finding jobs. However, in line

with their counterparts in other rich nations, U.S. refugees earn

low wages even after 10 years of residency.

CIS

estimated

in 2020 that the average new refugee in the U.S. imposes a fiscal

cost of about $60,000 in lifetime net present value. The

corresponding cost for refugees who enter as adults is $133,000.

Zachary

Ward, “The

Not-So-Hot Melting Pot: The Persistence of Outcomes for Descendants

of the Age of Mass Migration”, American Economic Journal:

Applied Economics, Vol. 12, No. 4, October 2020.

The

idea that Great Wave immigrants of varied nationalities disappeared

into a “melting pot” is an exaggeration. In 1880, large

differences in earnings (as measured by occupational status) existed

among immigrants of different nationalities. By 1940, the

grandchildren of those immigrants still exhibited about half of the

initial differences. Although this paper focuses primarily on Great

Wave immigrants, the author warns that “there are many reasons

to expect the persistence of ethnic gaps to be stronger for more

recent times.”

Indeed, a CIS report

finds that the grandchildren of Mexican immigrants still lag behind

white Americans in education and earnings. Immigration advocates who

brush aside concerns about assimilation need to address this

worrisome evidence.

Dafeng

Xu, “The

Effects of Immigration Restriction Laws on Immigrant Segregation in

the Early Twentieth Century U.S.”, Journal of Comparative

Politics, Vol. 48, No. 2, 2020.

The

ethnic enclaves in which Great Wave immigrants gathered eventually

withered away, leading to less residential segregation. According to

this paper, the process was aided by immigration restriction in the

1920s. The paper finds that residential segregation decreased more

rapidly among the immigrant groups that were most restricted, such

as Italians and Poles. The effect occurred mainly by denying ethnic

enclaves “reinforcements” in the form of new immigrants,

although the author also finds some evidence that return migration

became more likely among enclave residents compared to non-enclave

residents. The results suggest that, to the extent that the “melting

pot” operates, it can be strengthened by limiting

immigration.

Deniz

Gevrek, Cahit Guven, and Z. Eylem Gevrek, “The

Relationship Between Early-life Conditions in the Home Country and

Adult Outcomes Among Child Immigrants in the United States”,

Economics & Human Biology, Vol. 45, 2022.

Immigrants

who arrive in the U.S. as children generally have the benefit of

growing up with institutions that help them integrate into their new

society. However, this paper finds that the infant mortality rate in

the children’s sending country is negatively associated with

their academic performance in U.S. middle schools and with their

subsequent labor market outcomes as adults. The authors argue that

this association is causal. However, even if the relationship is due

to other factors, it is still a sobering reminder that long-term

exposure to U.S. institutions (including costly social programs)

cannot always overcome pre-existing differences. CIS has reflected

on this problem in several papers, including an analysis

of academic tests that include the scores of U.S. immigrants and

their children.

Paola

Giuliano and Marco Tabellini, “The

Seeds of Ideology: Historical Immigration and Political Preferences

in the United States”, NBER Working Paper No. 27238, May

2020.

While

previous papers analyzed the socioeconomic assimilation of Great

Wave immigrants, this one focuses on political assimilation. The

authors find that preferences for redistribution among Americans

today are correlated with the historical presence of immigrants.

Specifically, immigrants seem to have imported the political

ideology of their home countries and then spread those views to

natives. Whether this political effect of immigration is truly

“negative” will depend on one’s own political

views, but remember that any significant political shift, to the

left or to the right, usually involves social disruption.

Crime and Health Effects

Alexander

Billy and Michael Packard, “Crime

and the Mariel Boatlift”, Working Paper, October 2020.

Research

on the Mariel Boatlift usually focuses on the labor market impact.

(See Anastasopoulos et

al.

above.) This paper investigates the impact on crime. Compared to

similar cities, Miami experienced a 41 percent increase in the

murder rate, a 70 percent increase in the rate of robberies, and at

least a 25 percent increase in the rate of property crimes after the

boatlift. The authors caution, however, that extrapolating to

ordinary immigrants would be unjustified, since Fidel Castro added

inmates of prisons and mental hospitals to the ranks of the

Marielitos.

In a 2009 report,

CIS discussed the challenges of measuring immigrant crime. A

follow-up piece

in 2015 summarized recent developments, with particular emphasis on

choosing an appropriate baseline for comparison.

Brandyn

F. Churchill, Andrew Dickinson, Taylor Mackay, and Joseph J. Sabia,

“The

Effect of E-Verify Laws on Crime”, Industrial and Labor

Relations Review, forthcoming.

States

that mandated E-Verify

saw a 7 percent decline in property crime committed by working-age

Hispanics. The authors believe that the decrease in labor market

competition with illegal aliens steered Hispanic citizens toward

work and away from crime.

Mevlude

Akbulut-Yuksel, Naci H. Mocan, Semih Tumen, and Belgi Turan, “The

Crime Effect of Refugees”, NBER Working Paper No. 30070,

May 2022.

The

influx of millions of Syrian refugees into Turkey caused crime to

rise in the most affected provinces, although this study cannot

distinguish between Syrian and Turkish offenders. The authors

theorize that economic competition is one of the drivers of conflict

between the two groups.

Although massive refugee

flows are more associated with Europe, the U.S. may eventually

confront similar issues. For example, when the Biden administration

began accepting tens of thousands of Afghan refugees last year, CIS

warned that vetting

was woefully insufficient. An additional CIS report discussed

evidence that crime

rates among Afghan refugees in Europe are troublingly high.

Whether the U.S. will experience similar refugee crime problems

remains to be seen.

Philipp

Ager, James J. Feigenbaum, Casper Worm Hansen, and Hui Ren Tan, “How

The Other Half Died: Immigration and Mortality in US Cities”,

NBER Working Paper 27480, July 2020.

Analyzing

the aftermath of the 1924 immigration restriction, the authors

develop a measure of “missing immigrants”, meaning the

difference between the actual number of immigrants post-1924 and the

number expected based on pre-1924 trend lines. Cities with more

missing immigrants saw greater declines in infectious-disease

deaths. The authors argue that reduced crowding led to improved

sanitation in cities, boosting the health of immigrants and natives

alike.

The link between overcrowding and disease

became highly salient during the Covid-19 pandemic. As CIS has

shown, household overcrowding contributes to the spread of

respiratory diseases, including

Covid-19, and modern immigration has added

significantly to the overcrowding problem in the U.S. — just

as it did prior to 1924.

Melike

Dedeoğlu, Emrah Koçak, and Zübeyde Şentürk

Uucak, “The

Impact of Immigration on Human Capital and Carbon Dioxide Emissions

in the USA: An Empirical Investigation”, Air Quality,

Atmosphere & Health, Vol. 14, 2021.

This

paper shows that immigration to the U.S. increases the country’s

greenhouse gas emissions. While allowing that mitigating climate

change requires a multi-faceted approach, the authors argue that

policymakers should not ignore the role of immigration when devising

environmental policies. Previous CIS research has made largely the

same

point.

--

And Gavin Newsom's California leads the way in providing taxpayer funded benefits for immigrants:

29 Jun 2022

1,870

The sanctuary state of California will make history by becoming the first state in the nation to give food stamps to illegal aliens.

This week, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) announced a budget deal with Democrat state legislators that includes providing food stamps, paid for by California’s taxpayers, to illegal aliens 55 and older — the first initiative of its kind in the United States.

An executive with the group Nourish California told the Fresno Bee that the policy is historic for the state, saying, “California is once again making history by removing xenophobic exclusions to our state’s safety net.”

Expansion of the state’s CalFresh food stamps program will cost California’s taxpayers more than $35 million and about 75,000 illegal aliens are expected to enroll every year.

The move comes as Newsom’s budget deal will also ensure that California is the first state in the nation to provide taxpayer-funded health insurance to all of its 3.3 million illegal aliens.

Offering taxpayer-funded health insurance to its entire illegal alien population, the largest in the nation, is expected to cost California’s taxpayers about $2.4 billion annually. The plan is scheduled to begin in 2024.

John Binder is a reporter for Breitbart News. Email him at jbinder@breitbart.com. Follow him on Twitter here.

SOLUTIONS:

--Re: The Pending Mass Alien Amnesty Bill

--

Rep. Salazar’s Mass Alien Amnesty bill is basically mainly a con-job that open borders cheap labor Republicans plus leftist Democrats can enact any time this year UNLESS WE STOP THEM.

So please help CCN stop The largest Illegal Alien Amnesty in U.S. History and end MASS legal immigration!

URGENT: Contact your U.S. Representatives and Senators repeatedly and urge them to oppose any Bill which contains ANY Amnesty Bill provisions or provisions increasing Legal Immigration whatsoever...Insist they support an all-categories included zero-net MORATORIUM on Legal Immigration (which would still allow 150,000 settlers annually) plus a stand-alone Save Title 42 Provision

Also note that CCN is pro-Legal Immigrants but anti-Mass Immigration!

And Most Important to Note:

ONLY pushing CCN's all-categories-included zero Net MORATORIUM on Legal Immigration MAXIMIZES the chances of stopping this Horrendous Amnesty Bill.

Pushing any less restrictive number, as the two National Mass Immigration Management Groups do, will likely result in a Compromise Bill reducing the numbers by just a few hundred thousand at most..... a totally unacceptable result.

Indeed, since those two National Mass Immigration Management groups refuse to support any Moratorium Bill (like Rep. Gosar's e.g.)

THEY ARE DE FACTO ENABLERS OF CONTINUING MASS IMMIGRATION!!

URGENT:Contact your U.S.Representatives and Senators repeatedly and urge them to oppose any Bill which contains ANY Amnesty Bill provisions.

MULTIPLY your Impact by making a Tax-Deductible Donation to Carrying Capacity Network carryingcapacity.org NOW

Frankly, CCN needs money NOW to continue its Activism.!!!

CCN can thereby Intensify its Mobilization of its Activists all over the USA to oppose this bill

Indeed, CCN Activists stopped passage of a Mass Alien Amnesty Bill in December, 2019......

Our Activist Network has Clout!

---

And we reiterate::

ONLY pushing CCN's all-categories-included zero Net MORATORIUM MAXIMIZES the chances of stopping this Horrendous Alien Amnesty Bill.

Pushing any less restrictive number, as the Mass Immigration Management Groups do, will likely result in a Compromise Bill reducing the numbers by just a few Million at most..... a totally unacceptable result.

--

Donations are Tax-Deductible. Help CCN intensify our efforts. Please DONATE NOW by Credit Card at carryingcapacity.org. or by Check via U.S. mail to:

CCN’S

MAILING ADDRESS

Carrying

Capacity Network

P.O.BOX 457

San Francisco, CA 94104

Sincerely,

Carrying

Capacity Network,

Inc.

CarryingCapacity.org

CarryingCapacityNetwork.blogspot.com

CarryingCapacity.wordpress.com

Carrying

Capacity on ASAP-Coalition.org

Follow

CARRYING

CAPACITY on GAB: @CarryingCapacity &

Twitter: @CCNetworkOrg

--

Steve Camarota Discusses Housing Afghans in Hotels

Estimating the Illegal Immigrant Population Using the Current Population Survey

Related Articles

Republican State Legislators: Let’s Make Life Uncomfortable for Illegal Aliens

More from the Author

The Value of Foreign Degrees by Source Country

Why the Trump Administration Weakened Its Own Public Charge Rule

Defenders of the Public Charge Rule Have Their Day at the Supreme Court

The Center for Immigration Studies